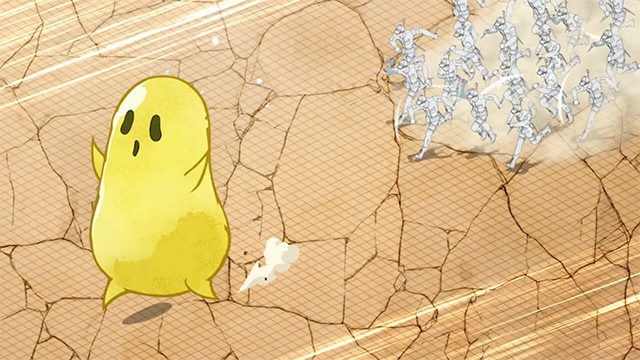

We just watched this excellent video by Rebecca Watson which discusses, among other things, the hygiene hypothesis. The hygiene hypothesis is the theory that early life exposure to a variety of allergens and benign microbes trains your immune system not to go apeshit over every little thing. If you’ve seen Cells at Work Season 1 Episode 5, you know all about this. Cedar pollen shows up. It’s big and bumbles about, but is essentially harmless. Until the immune system decides it’s an enemy invasion and causes harm (i.e. an allergy attack) trying to eradicate the pollen.

According to the hygiene hypothesis, if the body had enough exposure to harmless visitors early on, the immune system would chill and ignore the cedar pollen. No allergy apocalypse.

But the hygiene hypothesis is far from settled science. Or, as this journal article puts it:

Recent evidence does not provide unequivocal support for the hygiene hypothesis: […] asthma prevalence has begun to decline in some western countries, but there is little evidence that they have become less clean[.…] It is possible that a more general version of the hygiene hypothesis is still valid, but the aetiologic mechanisms involved are currently unclear.

Brooks, Collin; Pearce, Neil; Douwes, Jeroen The hygiene hypothesis in allergy and asthma, Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology: February 2013 – Volume 13 – Issue 1 – p 70-77

doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32835ad0d2

In other words, it’s possible that the hygiene hypothesis partly explains why some people get allergies and asthma while others don’t. It’s certainly not the whole picture. And if it is a thing, we don’t really know how it works.

In her video, Rebecca Watson mentions that the hygiene hypothesis goes back to at least the early 1800s, when doctors noted allergies and asthma were almost exclusively upper class diseases.

Hay-fever is said to be an aristocratic disease, and there can be no doubt that, if it is not almost wholly con- fined to the upper classes of society, it is rarely, if ever, met with but among the educated.

Blackley, Charles H. Experimental researches on the causes and nature of catarrhus æstivus (hay-fever or hay-asthma). (London : Bailliere, Tindall & Cox, 1873), 6, section 20, Wellcome Library, https://archive.org/details/b20418620/page/6/mode/2up, accessed April 18, 2021.

This piqued our interest. The strongest, most consistent evidence for the hygiene hypothesis is that farmer’s children get allergies and asthma far less than other children. Something about the rural lifestyle seems to be protective. Brooks, Pearce, and Douwes note while it “remains unclear which specific factors are most important, […] microbial exposures may play a role” (Brooks, Pearce, and Douwes, “The hygiene hypothesis”).

There are many pieces to this puzzle, but what if major contributors are being overlooked? We spent plenty of time in dirty outdoor pursuits as a kid, and we still wound up with allergies and asthma up the wazoo. Sure, there’s a genetic predisposition in our family, but what else could be going on?

What is a major difference between 1800s aristocrats and farmers? Time spent outdoors engaged in physical labor. This means there are two major contributors that appear to be overlooked in the literature: physical fitness and access to fresh air.

The available evidence indicates that physical activity is a possible protective factor against asthma development.

Eijkemans M, Mommers M, Draaisma JM, Thijs C, Prins MH. Physical activity and asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e50775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050775. Epub 2012 Dec 20. PMID: 23284646; PMCID: PMC3527462.

In addition, asthmatics can improve their heart and lung function via exercise, leading to reduced symptoms and increased quality of life. We’ve seen this in our own life. When we were on a water polo team, we were in amazing shape and could actually enjoy running a mile in P.E.! The jury is still out on whether exercise protects against allergies, but studies seem to indicate moderate exercise lowers inflammation. In other words, it helps your immune system chill out, which means less “ERMAHGAWD, CEDAR POLLEN!!! KILL IT! KILL IT! KIIIILLLL IIIIIT!!!” episodes.

Access to good air quality with plenty of ventilation is also an important factor, and it’s in increasingly short supply.

In the last several years, a growing body of scientific evidence has indicated that the air within homes and other buildings can be more seriously polluted than the outdoor air in even the largest and most industrialized cities. Other research indicates that people spend approximately 90% of their time indoors. Thus, for many people, the risks to health from exposure to indoor air pollution may be greater than risks from outdoor pollution.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Healthy housing reference manual. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2006, Chapter 5, https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/publications/books/housing/cha05.htm, accessed April 18, 2021.

Or to put it more succinctly:

Walking into a modern building can sometimes be compared to placing your head inside a plastic bag that is filled with toxic fumes.

John Bower, founder Healthy House Institute, quoted in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Healthy housing reference manual. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2006, Chapter 5, https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/publications/books/housing/cha05.htm, accessed April 18, 2021.

And you’re probably spending 90% of your time with your head stuck in that plastic bag. Unless you have a job like farming, which requires you to be outside most of the time. Even though we spent many hours gardening, hiking, and animal canoodling as a kid, we still spent the vast majority of our life indoors. Maybe if we’d grown up on a working farm our immune system wouldn’t have had as much exposure to toxins. See how it all comes together?

We hope that scientists will start investigating the indoor toxicity angle in particular. If the evidence backs our hypothesis, we hope it will drive policy changes that help make the great indoors a healthier place to be.